Undici in collaborazione con Puma Eyewear presenta #NoCage, il format che raccoglie le storie di 12 personaggi sportivi contemporanei e del passato, che hanno cambiato la storia dello sport superando le barriere e gli ostacoli grazie alla determinazione e alla forza di volontà.

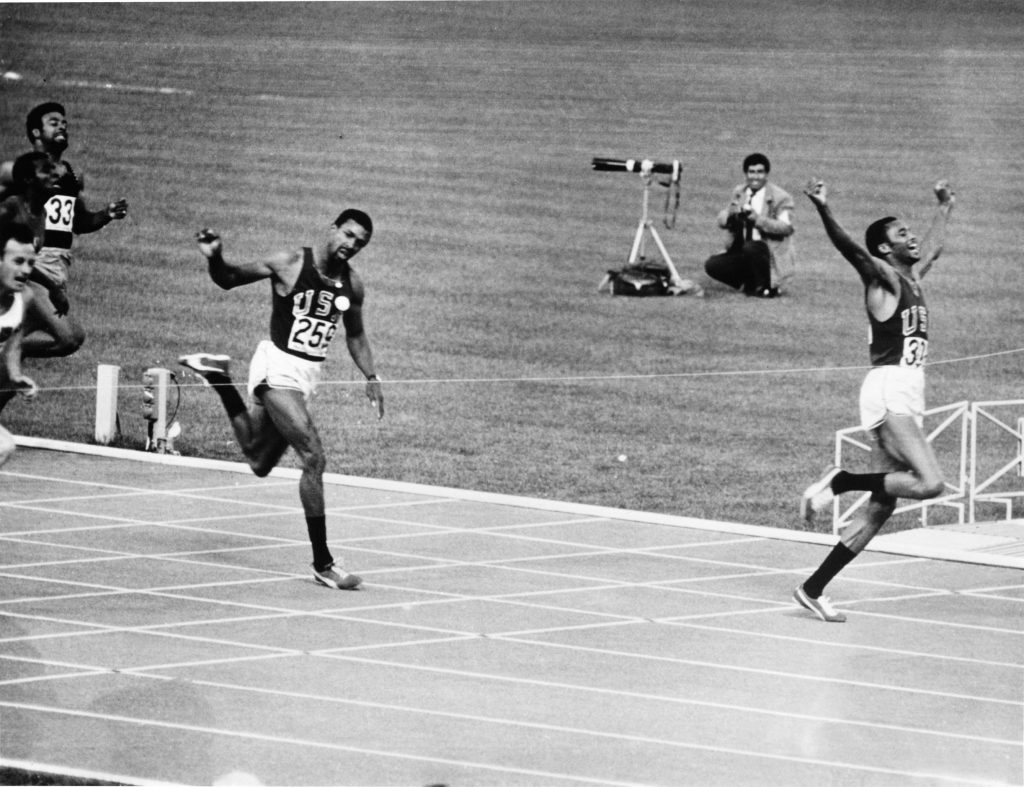

Il pugno destro, guantato di nero, teso al cielo senza arroganza. La sciarpa scura al collo e la testa china, in un raccoglimento intimo paradossale, con gli occhi del mondo intero puntati addosso. La medaglia d’oro scintillante, appesa al collo, che sembra pesare come un macigno. Tommie Smith è entrato nella storia così. Stretto per sempre, nel tempo fermo di un fotogramma. In cima al podio olimpico dei duecento metri a Città del Messico, il 17 ottobre del 1968. Come un Cristo nero in tuta olimpica americana, in un trittico da Golgota pop, affiancato dall’australiano Peter Norman e dal connazionale afroamericano John Carlos. Tre atleti formidabili, per cui non si spalancherà nessun regno celeste, ma l’inferno irreversibile dell’emarginazione, negli anni a seguire. Il giorno prima della premiazione, i tre hanno dato vita ad una gara memorabile. Sotto un cielo grigio di nuvole e afa, John Carlos è partito come un fulmine, bruciando quasi tutto quello che aveva in corpo: a 30 metri dal traguardo Smith, detto Tommie the Jet, lo ha superato in volata, sollevando le braccia al cielo mentre tagliava il traguardo. Norman, partito male, nei primi cento metri si è ritrovato in sesta posizione. Una spaventosa progressione finale ha permesso anche a lui di beffare Carlos, all’ultimo respiro.

La gara dei 200 metri maschili vinta da Tommie Smith

Il vincitore, Tommie Smith, con il tempo di 19”83, è il primo uomo a scendere sotto i 20” nei duecento metri. Il suo record resisterà undici anni, ritoccato nel 1979, sulla stessa pista, da Pietro Mennea da Barletta, ovvero l’alfiere ossuto di un altro sud, capace di affrontare la questione meridionale a colpi di volontà estrema. Ce ne sarebbe abbastanza, per il signor Smith, per incidere il proprio comunissimo cognome nella storia dell’atletica. Ma l’eroismo di quell’afroamericano dall’aria nobile, munito di barbetta rada da principe etiope, non è solo nell’essere il più veloce del mondo. Negli occhi scuri brilla tutta la sua vicenda umana, fatalmente roca come una ballata blues. Nasce il 6 giugno del 1944, il giorno in cui gli americani invadono la Normandia. Texano di Clerksville, negli anni cinquanta Tommie è solo un ragazzino smilzo, settimo di dodici figli, curvo tutto il giorno nelle piantagioni di cotone, con suo padre e i fratelli.

Un giorno contrae una polmonite devastante, quasi letale: mentre il petto gli brucia e tiene l’anima fra i denti, non può nemmeno immaginare che quei polmoni in fiamme lo isseranno sul tetto del mondo, solo qualche anno dopo. Intorno a lui il Texas vive ancora immerso in una soffocante segregazione razziale, come tutti gli Stati del sud. Esercitata implacabilmente nelle scuole, sui mezzi di trasporto, nei ristoranti e negli ospedali. All’orizzonte, fa capolino un pastore battista di Atlanta, armato di un sogno, strenuo predicatore della disobbedienza civile, della lotta non violenta per l’uguaglianza razziale. Quel Martin Luther King che, il 4 aprile del 1968, poco prima che Tommie Smith corra in Messico, viene freddato da un colpo di fucile alla testa, in un motel di Memphis. Quello che verrà definito secolo breve sembra vivere uno dei suoi picchi d’incandescenza: il 4 giugno viene ammazzato anche Bob Kennedy.

Il saluto di Smith e Carlos sul podio di Città del Messico

Il 2 ottobre del 1968, a Piazza delle Tre Culture, si consuma il massacro di Tlatelolco. Militari in armi, carri blindati e veicoli da combattimento aprono il fuoco sulla folla che protesta, ammazzando circa trecento manifestanti. E’ il bagno di sangue che apre le Olimpiadi messicane. Un anno prima, Harry Edwards, sociologo di Berkeley e discobolo di medio cabotaggio, ha dato corpo a un’utopia chiamata Ophr – Olympic program for human rights. Gli atleti afroamericani che aderiscono al progetto pretendono allenatori di colore da aggregare allo staff della squadra americana e contestano duramente la riammissione alle Olimpiadi del Sudafrica dell’apartheid. Soppesano, come gesto estremo, la possibilità di boicottare in blocco le Olimpiadi. Alla fine rinunciano a disertare le gare: optano per una protesta simbolica, esercitata sotto i riflettori di un’irripetibile ribalta mediatica, decisa in autonomia da ogni atleta.

Un distintivo, simile a una coccarda, contrassegnerà chi avalla l’idea di Edwards. Smith e Carlos, iscritti all’Università di San Josè, dove si esercitano i velocisti più forti d’America, sono profondamente imbevuti degli umori di protesta, che spirano sulla California. Corrono come schegge e studiano sociologia. Tommie Smith , in particolare, è affascinato dalla costituzione e dai discorsi di Thomas Jefferson. Prima delle Olimpiadi messicane vince tredici record universitari nell’atletica leggera. John Carlos, viene da Harlem. Figlio di un veterano della prima guerra mondiale, nato da due schiavi, ha alle spalle un’infanzia di strada, passata ad affinare la propria stupefacente rapidità, rubando sui treni in corsa. La stessa velocità che gli permetterà di uscire dal ghetto, vincendo una borsa di studio per San Josè.

John Carlos lascia il villaggio olimpico dopo essere stato sospeso per il gesto del pugno alzato sul podio dei 200m (Afp/Getty Images)

Subito dopo la gara olimpica, elaborano un gesto definitivo, seppur non violento. Vogliono provare a trasferire la potenza eversiva del Black Power nel circo fino a quel momento asettico delle Olimpiadi. Ripensano a Jesse Owens, campione afroamericano, che trionfò alle Olimpiadi di Berlino, nel 36, davanti ad un esterrefatto Hitler. Franklin Delano Roosvelt, al ritorno in patria, lo trattò molto peggio del Führer. Il presidente in carica, in piena campagna elettorale, non volle alienarsi l’elettorato degli Stati del Sud. Evitò accuratamente di invitarlo alla Casa Bianca, relegando l’atleta di colore ad un mesto doppio ruolo: utile vessillo della superiorità yankee, nelle cerimonie olimpiche, e negro come tutti gli altri, a riflettori spenti. Smith e Carlos non vogliono seguirne il destino. Stanno per scrivere un capitolo nuovo, nella storia afroamericana. Nel sottopassaggio che conduce dagli spogliatoi al podio Peter Norman, l’australiano medaglia d’argento, ne osserva incuriosito la preparazione rituale. Ogni gesto che compiono, nel sottopassaggio, rinvia ad una semiotica precisa. Si tolgono le scarpe, evocando una povertà vissuta sulla propria pelle. Carlos si mette una collanina di pietre al collo: ogni sassolino è il ricordo di un nero linciato, mentre lottava per i propri diritti. Smith alzerà il pugno destro, segno della forza del popolo nero, Carlos il pugno sinistro, simbolo della sua unità. Hanno un piccolo problema: Carlos ha dimenticato i suoi guanti neri al villaggio. Ce li ha solo Smith, premurosamente acquistati da sua moglie.

[widegallery id=”15319″][/widegallery]

Norman, ormai definitivamente sedotto dalla causa dei suoi compagni di podio, dirime la questione: «Mettetevi un guanto a testa. E date un distintivo anche a me. Sono con voi, anche se sono bianco». Norman fa parte dell’Esercito della salvezza, movimento internazionale evangelico dalla forte impronta sociale. Nella sua Melbourne ha visto gli orrori della discriminazione degli aborigeni. Si addobba con la spilletta dell’Ophr e sale sul podio. Smith alza il pugno destro, Carlos il sinistro. Nel frattempo, nello stadio messicano ammutolito, risuona forte The star spangled banner, trionfale inno degli Usa che sembra non appartenergli nemmeno un po’. «Ve ne pentirete per tutta a vita» gli digrigna nelle orecchie, a cerimonia finita, Payton Jordan, capo della delegazione USA. La reazione di Avery Brundage, presidente del Comitato Olimpico internazionale e noto per le malcelate simpatie naziste, è violenta quanto immediata: i due vengono sospesi dalla squadra americana ed espulsi dal villaggio olimpico. Accusati di aver ricevuto soldi di nascosto, per boicottare gli Usa. L’ostracismo è implacabile: la loro punizione deve essere un monito, per chiunque desideri seguirne le orme.

[widegallery][/widegallery]

Ispirati dall’iconica sneaker da corsa Bolt, gli occhiali Ignite 600 sono realizzati in acetato iniettato di alta qualità che presenta degli inserti in materiale ammortizzante sulle stanghette per una vestibilità e una stabilità senza pari. Le lenti a specchio a contrasto, flash o uniformi, creano effetti di grande impatto nelle varianti corallo e argento, bianco e rosa o cioccolato.

Smith, l’uomo più veloce del mondo, a venticinque anni è già un ex corridore. Costretto a campare lavando auto, mentre il Ku Klux Klan gli fa recapitare a casa, con puntuale regolarità, quintali di sterco alternati a minacce di morte. L’esercito lo espelle con disonore, “per attività antiamericane”. L’esclusione diventa una salvezza: eviterà la partenza per il Vietnam. Carlos, dal canto suo, oscilla tra brevi esperienze nel football americano alternate ad impieghi da scaricatore, nel porto di New York, e da buttafuori nei night. Dopo anni di minacce telefoniche, ricevute nel cuore della notte, sua moglie si uccide. Norman, in Australia, non se la passa meglio. Supera tredici volte il tempo di qualificazione per i duecento, e cinque quello per i cento, ma la sua Federazione lo esclude dalle Olimpiadi tedesche del 1972, senza concedere spiegazioni. Tenta la via del football, ma una lesione al tendine d’Achille lo costringe a smettere. Insegna educazione fisica, lavora nei sindacati e rimpingua il magro stipendio dietro il banco di una macelleria. Non viene nemmeno invitato alle Olimpiadi di Sidney del duemila. Dove, con il suo 20”06 messicano, imbattuto record australiano, avrebbe vinto l’oro.

I suoi due amici afroamericani, col passare degli anni, vengono riabilitati. L’Università di San Josè si ricorda di loro, assumendoli come insegnanti di educazione fisica e dedicandogli perfino un monumento. Avranno la possibilità di allenare, vivere immersi nello sport, continuare a raccontare la propria storia alle nuove generazioni. Norman no: per lui l’emarginazione sarà definitiva. Quando muore d’infarto, il 9 ottobre del 2006, a reggere la sua bara ci sono i suoi amici Smith e Carlos. «A Città del Messico non eravamo due neri e un bianco: eravamo tre esseri umani. Se a noi due ci hanno preso a calci nel culo a turno, Peter affrontò un intero paese e soffrì da solo. Però non si pentì mai del suo gesto. E nemmeno noi».