Undici in partnership with Puma Eyewear presents #NoCage, a collection of 12 stories of past and contemporary athletes that have changed the history of sports, overcoming the barriers and obstacles in their path thanks to determination and willpower.

There is a time to sow and a time to reap. Sometimes only a brief interval passes between the two, while in others one has to wait a little longer. Considering her talent, the world of Italian fencing waited much longer than one might have expected for Elisa Di Francisca, and she in turn has waited 30 years for her first Olympics. But it was worth it. That gold medal, won in London in 2012, in a somewhat overdue début at the Games, was the culmination of a long process for the fencer from Jesi. And that bout, watched again today, is a perfect compendium of the superlative quality of Di Francisca’s fencing skill. A style of fencing that rests on the foundations of perfect technique, alights on the thermals of pure instinct, and finds itself in a state of cool mental clarity that never fails, even in the most difficult moments. The London gold was the result of two assaults decided in a minute of extra time: sixty seconds, a priority given at random – the first one to touch wins. As a relatively frequent occurrence in fencing, there has even been a failed attempt to introduce the mort subite – as the French call it –, to football with the golden goal, however, having to face this situation twice in a row, in both a semifinal and an Olympic final, presents a unique challenge for both oneself and the opponent.

First, Elisa faces Nam. She takes it with a comeback. At 1 minute from the end, the score is 9-5 for the Korean. Thirty seconds later the score is 10-10, but the passivity of the bout is on her side, and she touches. In the final against Arianna Errigo, Elisa goes straight into a 7-3 lead, but at the turn of the second and third bout, the partial score swings to 8-1, and she finds herself losing 11-8 only 36 seconds from the end of the assault. Ninety per cent of athletes facing a situation of this kind would have a psychological breakdown. Elisa did not. In an interview available through the YouTube channel of the Olympic Games, the fencer from Jesi relives that moment: “I was tense; I tried to find a middle ground between the frenzied excitement, the desire to recover and the tranquility to land the thrust.” The point is that while all this whirled around in her head, she was alone with her demons, without a coach to support her, because her opponent, Arianna Errigo, is her teammate, and as per regulations, her coach cannot be present during bouts between members of the same national team. Her brain processes a perfect strategy and it takes two seconds to complete the comeback win, again during the extra minute. Coldness, lucidity, and even a bit of luck because Errigo defends, but does not react to the decisive blow with a riposte. Gold. Her first. At 30.

Elisa Di Francisca on becoming Olympic Foil champion at London 2012

The fundamentals

Di Francisca is a pure talent raised according to the highest traditions of Italian fencing. In the previously cited interview published on the Youtube channel of the Olympic Games, she explains how her approach to fencing mirrors her approach to life: “I go by my gut feeling, I do not have strategies, I am very instinctive. I do what I need to do in the moment”. The truth is that behind her “gut feeling” lie outstanding fundamental skills. Watching Elisa fence is like watching a tutorial on foiling. The breadth of her guard, the degree to which her knees are bent, the upright position of her back, the depth of her thrusts. Everything goes by the book, and in this respect, very little is instinctive. This is the fruit of 27 years of fencing, of five days training every week and a specifically designed athletic preparation program focused on the agility of the legs and very few weights. Di Francisca never makes a movement that is not strictly necessary, it is her simplicity in human form that led her up onto the platform. She often touches thanks to textbook moves that every coach teaches his students in their first lessons.

As a good native of Jesi, she has mastered the art of the thrust on her opponent’s advance, but if I had to choose the thing that Di Francisca does best, for me it would be the advance-lunge. I have rarely seen a fencer touch with the same frequency using an action that is only simple on paper. An action that, to be as effective as it is for Di Francisca, must be carried out to perfection in terms of the two fundamental principles of fencing: time and extent. If I try to think of another world-class sportsperson capable of ‘earning’ so much with the apparent simplicity of their play, I only can think of Tim Duncan and his basket shot leaning against the scoreboard after a pivot turn on his foot. Here, Elisa is the Tim Duncan of fencing: inconspicuous, maybe, but technically perfect. And if she has had to wait so long to be granted the greatest satisfaction of her life, it is only as a result of contingent factors, such as the fact that her early career coincided with the last years of Giovanna Trillini, the most important years of Valentina Vezzali, and the most explosive seasons of Margaret Granbassi.

Italy’s Elisa Di Francisca celebrates her victory over Italy’s Arianna Errigo at the end of their women’s foil gold medal fencing bout as part of the London 2012 Olympic games, on July 28, 2012 at the ExCel centre in London (Alberto Pizzoli/Afp/GettyImages)

A dance

Step forward, step back, step forward and lunge. One-two, one-two, one-two-three. Watching Di Francisca move on the platform by shifting the weight of her body from heel to toe is like watching a ballet. She catches the eye of even the least experienced spectators of fencing. It is about rhythm, yes, but also elegance. Without doubt her physique of an étoile at La Scala helps, but the real secret is to be found in Elisa’s childhood. As a child, before she discovered fencing, Elise did ballet. Starting at five, she only danced until she was seven, but when she swapped her tutu for a plastron and conductive jacket and abandoned her demi-pointe to grip the foil, something of dance remained with her.

Her movements are so precise and composed that they almost appear prim, and if you observe her fencing action, she gives the impression of being in front of a slow motion act. But it is not a question of speed, which is not lacking – if it were, she would not touch so often –, if anything, it is a matter of cleanliness. There is no other player in the world that conveys the same sensation [of “cleanliness”]. Whether this is the merit of her superlative training in fencing or the countless pliés and rond de jambes that she did in front of the mirror between the ages of five and seven, is not sure, what we do know is that in 2013, as a newly crowned Olympic champion, Elisa returned to dance [in the television production] Ballando con le stelle (Dancing with the Stars). And she also won here.

Learning from the best

Although she still bears the signs of her early training in ballet, Elisa became aware that the excessive rigor of ballet was not for her early on. Looking for a new challenge, she decided to change sports, and given the city where she grew up, her choice was almost forced. “In Jesi, either you fenc or you fence” (ipse dixit taken from an interview for Sky Sports before the 2012 Games in London), except if your name in Roberto Mancini. But that’s another story. The story that interests us was started by Ezio Triccoli, an Italian Army Staff Sergeant who fell in love with fencing during his detention in the South African prison camp of Zonderwater during World War II. Before Triccoli, in Jesi, fencing did not exist. After Triccoli, Jesi would become the capital of Italian fencing. It was Triccioli who trained extraordinary champions like Stefano Cerioni, Giovanna Trillini and Valentina Vezzali, and it was Triccioli who put Elisa Di Francisca on the platform, beginning her technical development before he died in 1996, saying to Elisa’s mother: “I leave the gold [medal] in your daughter’s hands.” Think of a talented young girl who found herself training alongside athletes who had won 20 Olympic medals for Italy, every day. With two of them, Elisa formed such a bond that they would become her coaches during two different times in her life. Stefano Cerioni would replace Triccoli, accompanying her as her technical coach to the 2010 World Cup title in Paris and gold in the London Games of 2012. When Following Cerioni’s farewell – who gave up his badly paid contract with Federscherma Italiana, to accept a post with the Russian Fencing team –, Giovanna Trillini took over, continuing Elisa’s preparation for Rio 2016.

[widegallery][/widegallery]

And while there has always a sense of competitive mutual respect and fierce rivalry with the third protagonist, Valentina Vezzali, the pair’s sporting relationship has never progressed beyond that of teammates. They are just too different. In 2013, when Vezzali returned the World Championships in Budapest after her last period of maternity leave, she found herself in a team that had a different spirit, a spirit that was much closer to Elisa’s more theatrical character, and was forced to adapt to being a star of the balletic rituals that her compatriot invented before each assault. On Youtube, there is an interview with Datasport in which Elisa is presented with a list of fellow fencers and asked what she would like to do in their company. In her riposte, she includes going out dancing with Aldo Montano, a nice dinner with Arianna Errigo, a game of volleyball with Andrea Baldini, and a karaoke night with Andrea Cassara, but when the reporter gets to Valentina Vezzali, Elisa stops and thinks for a bit, then, giggling with embarrassment, she says: “An assault. Absolutely”. She parried, then suspended the action before giving the right answer: simultaneously sincere and diplomatic. The sense is that beyond the competitive context, Di Francisca and Vezzali do not frequent each other. In fact, they have been next door neighbours for much of their lives, but they simply do not want to hang out. On the athlete, though, Elisa has no complaints. Di Francisca has learned something from each of the extraordinary athletes and coaches with whom she grew up, and has even gone one step further, creating her own polished style of instinctive fencing, a style that is elegant, smart and simple, and virtually indisputable.

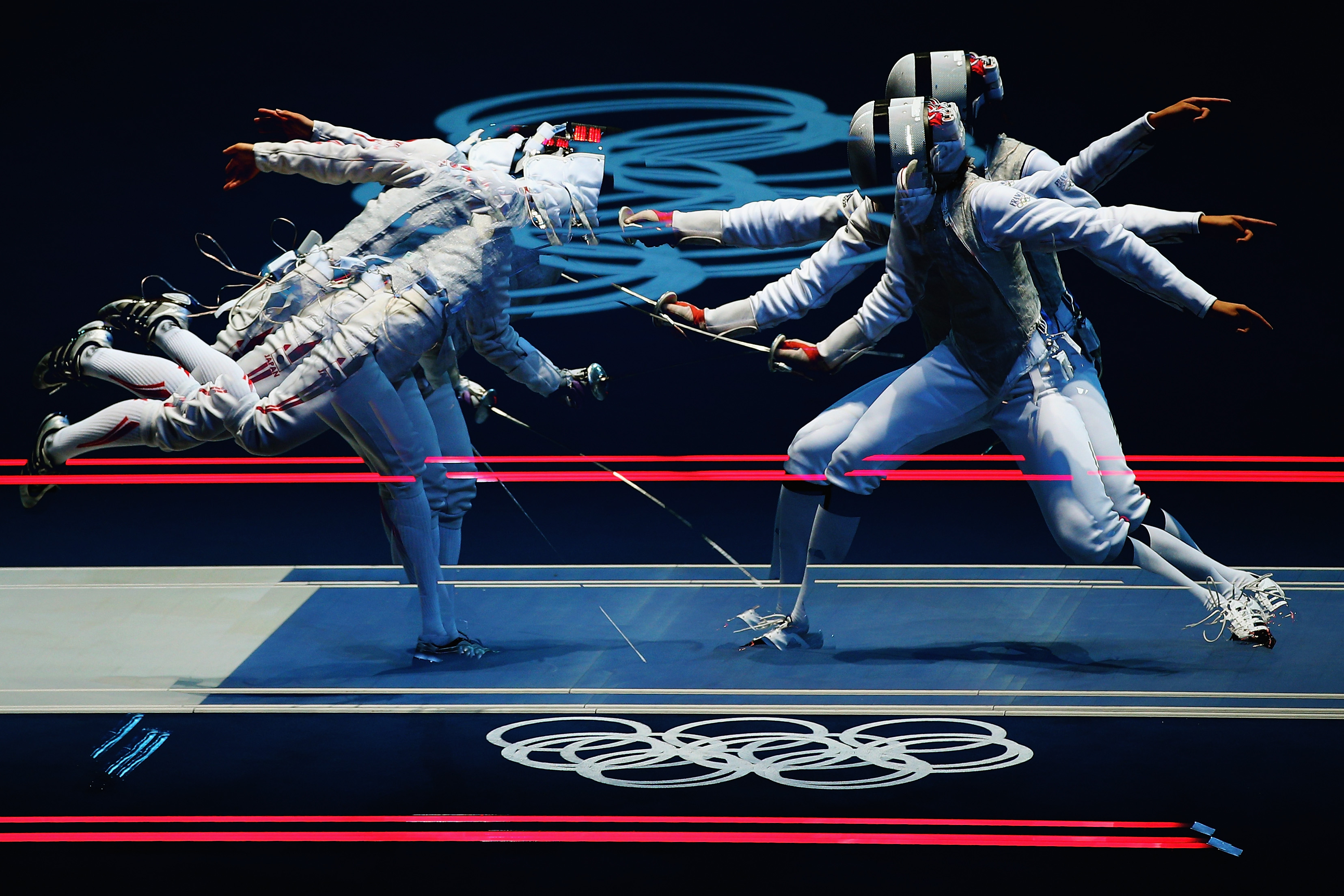

Carolin Golubytskyi of Germany competes against Elisa Di Francisca of Italy in their Women’s Foil Individual Fencing round of 16 match on Day 1 of the London 2012 Olympic Games at ExCeL on July 28, 2012 in London, England (Hannah Peters/Getty Images)

Burnt Youth

And to think we almost lost such a great talent. At eighteen, driven by the same instinct that earned her a ranking amongst the world’s greatest athletes, Elisa had given up fencing. She had lost her desire to win, the white uniform had begun to feel too tight and she preferred jeans, miniskirts and going out with friends. Bearing the weight of expectations can be difficult. It takes sacrifice and commitment, and sometimes it can be too much. When she quit, Di Francisca was already a promising star of Italian fencing. She had already won several national youth titles and was on the threshold of important international competitions in her category, but that did not stop her from leaving. Also guilty was her boyfriend of the time, who was definitely jealous, pressing, and even violent. To be with him, Elisa gave up a year of fencing, but then during a fight he hit her and she decided that their relationship was over. She left him, but did not report the violence, stating that “I also raised my hands”, but she understood that it was not love. Her real love was still reserved for fencing. It took time to get back into it, a few years at least, and she basically threw away her remaining seasons in the under 20 category, but if you scroll through her résumé, it is impossible not to notice the contrast between those unfortunate placings in the youth category and her successes of today. This said, by 23, she was already in the National fencing team. She won gold at the 2004 World Championships in New York, silver at Turin in 2006, and gold in Antalya 2009, moving in and out of the blue team, alternating with Margherita Granbassi and Ilaria Salvatori, and only becoming a permanent fixture when she Giovanna Trillini retired, until she came into her own, exploding onto the scene to take the world title in Paris in 2010, with which she officially won her placing amongst the world’s top fencers.

Sweet home Jesi

“There is no place like home,” said Dorothy Gale as she clicked the heels of her ruby slippers three times to leave Oz and go back to Kansas City. Elisa Di Francisca thinks exactly the same way. Just look at the nickname she chose for her Twitter account, @ElisaLovesJesi, to understand how close her ties to the city where she was born really are. Her world is there, in that little town of 40,000 inhabitants in the province of Ancona. With old friends, her parents, her siblings Martina and Michael (who both have a past and present in fencing, respectively), with the Fencing Club gym, which she continues to call “my home”. When asked what she remembers with the most affection of London 2012 during the interview for the Olympic Youtube channel, she answers: “The face of Stefano (Cerioni, ed), my coach, my brother, my sister, my father and my mother”. She was in London, the queen of the Games, but her heart had never actually left Jesi.

Arianna Errigo, Elisa Di Francisca and Valentina Vezzali of Italy sing the national anthem after receiving their medals after competing in the Women’s Foil Individual Fencing matches on Day 1 of the London 2012 Olympic Games at ExCeL on July 28, 2012 in London, England (Hannah Peters/Getty Images)

The last Olympics

Rio 2016 is a milestone in Elisa Di Francisca’s career. And almost certainly the last competition with such importance. She is 34 years old and has never had any intention to go beyond the age of forty like Valentina Vezzali and Giovanna Trillini. Here too, she is different from them. While she has not yet announced her retirement, the signals are clear. Coach Andrea Cipressa has begun preparing for the Tokyo 2020 project with a team that does not rely on her. He would never have given up on Di Francisca if she had not backed off. No one ever would. Brazil, will thus be her second and last Olympics, and at the same time, the first with a title to defend. With another gold she would have a 100% win percentage at the Olympic Games and would close her career on a high, receiving what she has earned during her long wait for the deserved position of the best.