Undici in collaborazione con Puma Eyewear presenta #NoCage, il format che raccoglie le storie di 12 personaggi sportivi contemporanei e del passato, che hanno cambiato la storia dello sport superando le barriere e gli ostacoli grazie alla determinazione e alla forza di volontà.

Ribelli, e rivoluzionari, si nasce. E Boris Becker, modestamente, lo nacque. Parafrasando Totò. “Il ragazzo dei sogni” era ribelle già dai capelli, color carota da ragazzo (anche se ora curiosamente biondo oro). Era ribelle nel restare giornate intere al circolo del tennis dove lo parcheggiava il papà – grande appassionato – quand’aveva appena cinque anni, e dove vinse il primo torneo, a otto. Era ribelle nel decidere subito che la sua vita sarebbe stata quella e da impegnarsi talmente tanto che il Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione gli concesse una dispensa speciale, consentendogli di abbandonare la scuola dopo la licenza media. Ed era ribelle nel picchiare più forte che poteva qualsiasi palla gli arrivasse a tiro, a rischio di spararla fuori di metri e di beccarsi il nomignolo, allora dispregiativo, di Bum Bum. Perché, all’inizio, da junior, Boris da Leimen, a due passi dalla colta Heidelberg, era il Pierino della situazione, una delle promesse guidate dalla capo-classe Steffi Graf. Ma aveva quel qualcosa in più che faceva intravedere una determinazione decisiva, dietro una corporatura solida e muscoli che necessitavano di cure particolari e di allenamenti più duri di chiunque altri per poter incanalare quell’impressionante potenza all’interno delle righe del campo. Come scommetteva Boris Breskvar, oggi guida della promessa Dominic Thiem: «Becker poteva saltare e tuffarsi su qualsiasi colpo, temevo sempre che si facesse male, è nato combattente».

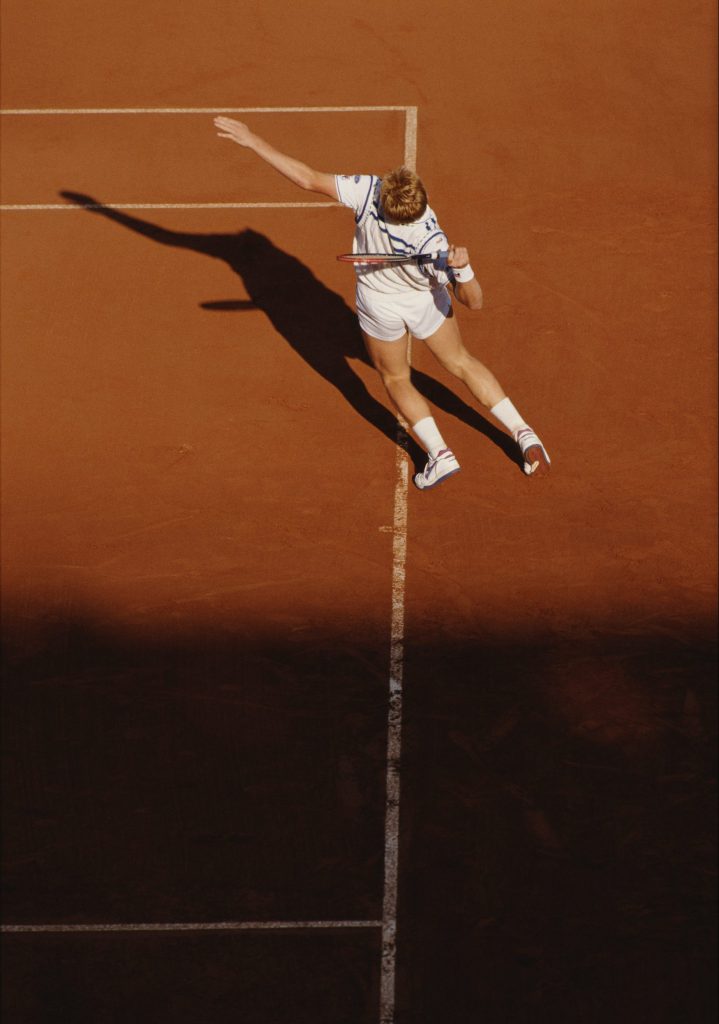

Boris Becker durante un match contro Thomas Muster nella finale dell’ Atp di Monte Carlo, nel maggio del 1995 (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

Non aveva paura di niente, Boris. Da calciatore, eccelleva come portiere, e si esaltava nelle parate più azzardate. Da tennista, forzò le remore dei genitori e firmò il patto col “Mefisto”, “Dracula dei Carpazi”, il baffuto Ion Tiriac, che si presentò a casa sua con un contratto a vita: l’ex giocatore, poi fortunato manager di attori come Nastase, Vilas, Leconte, Panatta, investiva a occhi chiusi sul futuro del ragazzo prodigio, chiedendo in cambio dedizione assoluta e carta bianca sui futuri business. Era innovatore, ed era motivatissimo, nei durissimi allenamenti col coach-mamma, Gunther Bosch, allenamenti tennistici, ma soprattutto fisici, dove squat, scale, scatti in pista s’accompagnavano anche al taglio della legna in altura, e ad altre stranezze alla Rocky Balboa del cinematografo. All’alba degli anni ’80, Boris da Leiden era, soprattutto, l’apripista di un nuovo, appassionante, tennis – che rimpiangiamo oggi fortemente -, servizio-risposta-volate a rete a cercare prima possibile il punto con la volée. Mentre, tutt’attorno a lui, e al grande rivale, Stefan Edberg, fioriva il “corri e tira” di Bollettieri, evoluzione sul cemento dei regolaristi da fondocampo di scuola-Borg. Cosicché quel lampo rosso spiccava ancor di più, e sempre più forte.

[widegallery][/widegallery]

La nuova collezione eyewear sportstyle di Puma rende omaggio alle “Suede”, le famose sneakers che dal 1968 rappresentano la quintessenza del brand tedesco. Le eleganti stanghette in Alcantara ® e le lenti colorate danno a questa collezione un tocco di freschezza, mentre la montatura in formato diva o rettangolare contribuisce a creare uno stile vintage ma moderno, certamente semplice e divertente da abbinare.

Becker era semplicemente diverso, in tutte le accezioni anche negative che il termine comporta. Diverso in quel servizio così caricato sulle gambe, diverso nella tosse nervosa che lo prendeva e non lo abbandonava nei momenti di massima tensione, diverso nel risolvere le situazioni più difficili uscendo dalla trincea con la baionetta – pardòn, la racchetta in pugno -, magari dopo una gran spallata di dritto, con la faccia feroce e determinata per affondare la volée. Una, due, tre volte, saltando di qua e di là coi suoi famosi tuffi. Finché l’avversario, oppresso, soffocato, impressionato, non vedendo più vie d’uscita, s’arrendeva. Era diverso anche nel riprodurre il fenomeno della precocità, allora ancora in voga fra i ragazzi neo-professionisti proprio perché il gioco non era così monotematico. Così, nel 1985, folgorò il mondo, non solo il tennis, sbucando dal nulla e vinse ad appena 17 anni e 227 giorni, il torneo più agognato da tutti, Wimbledon. Lui, il più giovane di tutti, “il ragazzo della porta accanto” con gli occhi azzurri che folgorano, parlava con la freschezza dei suoi anni ma diceva sempre cose interessanti, prendeva posizione, non rinunciava mai alla lotta.

Ribelle, proprio come in campo. Dove tutto, per lui, era più complicato e diventava tragedia, soprattutto sul mitico Centre Court: per gli altri, semplicemente, IL Tempio, per lui, “Il mio giardino”, teatro di sette finali, ma di “solo” tre trionfi. Per Bum Bum nulla era comune, nulla poteva essere assicurato. A cominciare da quell’indimenticabile edizione dell’85, quando domò Nystrom solo per 9-7 al quinto set e, subito dopo, contro Mayotte, si storse una caviglia come l’anno prima, quando se l’era rotta contro Scanlon e s’era dovuto operare. Impaurito e dolorante, andò a rete per stringere la mano all’avversario e ritirarsi, quando Tiriac gli urlò:«Tre minuti, tre minuti». Suggerendo lo stop medico e il salvataggio, dopo i 20 minuti che ci vollero prima che il trainer, arrivasse davvero in campo.

Con quelle premesse, anche se alla vigilia s’era aggiudicato il tradizionale prologo, al Queen’s, nessuno avrebbe scommesso che Boris avrebbe vinto per la prima volta i Championships, superando in finale lo specialista d’erba Kevin Curren. Nessuno, del resto, avrebbe pensato al bis consecutivo l’anno dopo, e invece Boris ci riuscì, stoppando fra l’altro in finale il sogno verde di Ivan Lendl. E ben pochi avrebbero pensato che avrebbe bucato clamorosamente il 1987, scivolando contro l’anonimo Peter Doohan, e che avrebbe vinto una sola volta, dall’88 al ’91, cedendo due volte in finale contro Edberg e Stich.

Becker vs Curren, Wimbledon 1985

Ma Becker era Becker proprio nella sua ribellione alle consuetudini, ai pronostici, alle ovvietà. Come nel 1992, quando sembrava evidente a tutti la necessità di attaccare il più possibile Andre Agassi, per evitare di essere sfiancato nella ragnatela da fondocampo. E invece Boris si intestardì, nel suo “giardino”, a vincere giocando come il Punk di Las Vegas (che aveva al suo angolo un certo John McEnroe). Così come nel 1995, a dispetto dello scetticismo comune, volò ancora fin sotto il traguardo, per arrendersi solo allo straordinario Pete Sampras, dopo avergli strappato un tie-break di speranza. Tenendo vivo l’ennesimo sogno come voleva il suo personaggio quasi epico. Becker era un ribelle. L’erba era il suo campo:«Mi piaceva prendere rischi». Rischi calcolati che facevano storcere il naso a papà-Tiriac: «Un tennista deve pensare poco». Così come storceva il naso la sua Germania che pure l’adorava e riempiva completamente gli stadi, a Francoforte ed Hannover per il Masters. «Penso che questa vittoria cambierà il tennis in Germania perché prima non abbiamo avuto un leader», aveva predetto, del resto, Bum Bum un attimo dopo il trionfo dell’85. Ma aveva presto aggiunto, spegnendo gli ardori:«Il tennis è importante, ma non è la cosa più importante della vita». Quello che proprio aveva taciuto fino all’ultimo al suo popolo era che lui, l’eroe ariano con la sua pelle bianchissima, lui così bravo nel risollevare l’orgoglio tennistico e sportivo nazionale dopo i fasti che risalivano addirittura al Barone Von Cramm negli anni ’30, avrebbe sposato Barbara Feltus una bellissima modella, di colore. E il suo popolo non approvò. Odiò “la strega negra”. Non lo perdonò anche se aveva pagato milioni di marchi di tasse arretrate per rinnegare la residenza fiscale di Montecarlo e vivere a Monaco di Baviera, e tifare per l’amatissimo Bayern.

Boris Becker durante i quarti di finale maschili a Wimbledon nel 1993 (Bob Martin/Getty Images)

Purtroppo il ribelle in positivo dello sport non si è ripetuto nella vita, Boris ha sbagliato spesso strada ha avuto una figlia illegittima in circostanze di cui vergognarsi, s’è buttato col solito ardore in tante imprese imprenditoriali ma non ha segnato i gol che ha fatto sul campo da tennis, non è salito al numero 1 del mondo, non ha vinto altri trofei da aggiungere ai sei Slam, collezionando piuttosto due matrimoni, un divorzio, quattro figli, e qualche scandalo. Come telecronista, non bucava lo schermo, come allenatore del numero 1, Novak Djokovic, si è riscoperto maestro del servizio e della spinta offensiva. Mai allontanarsi troppo oltre la linea di fondo, meglio rischiare un metro avanti e comandare subito lo scambio che cederlo, un metro indietro. Un bel ribelle.

[widegallery][/widegallery]